Al-Zawahiri strike is good for American democracy

Our national cohesion would be aided if we can keep terrorists at bay without massive troop deployments abroad

How can an extrajudicial killing of a foreign national living abroad possibly benefit American democracy?

Let me explain.

Since the end of World War II, Americans have had deeply mixed feelings about America’s role as a global superpower. On the one hand, the public has supported efforts to counter foreign actors that threaten our security or that of our close allies. On the other, Americans are uncomfortable with the concept that we have to shoulder the lion’s share of the burden of maintaining global security - especially when it comes to long term deployments of our troops and engagement in conflicts that lead to American casualties. This was true of the unpopular Korean and Vietnam conflicts, which were extensions of the Cold War, and the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This tension has led to a division between government elites, especially those in the national security establishment, and grassroots sections of the American public. By and large, the elites have seen the expenditures of blood and treasure as the unfortunate burden of global leadership and protection of the democratic liberal order. The grassroots have questioned the necessity of these tremendous sacrifices, claiming the elites are out of touch with most Americans.

While of course there are notable exceptions, especially public backlash to Vietnam, American presidents have felt comfortable advocating for assertive American internationalism, and at times the use of force, first to counter the Soviet Union, then to reverse Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, and then, following the 9/11 attacks, to forcefully combat al Qaeda and likeminded groups.

Then enter one Donald J. Trump.

Trump understood the public resentment to American internationalism and capitalized on it to his political advantage. During his first presidential campaign, he took the extraordinary step of criticizing the political elites, and even military leaders, for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Recall, he took aim at the favored candidate of the Republican establishment at the time - Jeb Bush - and pummeled him relentlessly on the Iraq War - even though Jeb had absolutely nothing to do with either the decision to go to war or its execution. Republican primary voters reacted enthusiastically to these ideas. Jeb Bush had no effective response. He performed anemically in the early primaries and was forced to withdraw by February 2016.

Fast forward to 2020.

Despite a brief flirtation with advocating for “victory in Afghanistan” (a policy foisted on the reluctant Trump by national security advisor H.R. McMaster), Trump spent much of his presidency calling for a departure from Afghanistan and searching for an exit ramp. Trump eventually found that exit ramp through a negotiated withdrawal agreement with the Taliban setting the terms for complete American troop departure by May 2021. Doubling down on his belief that anti-national security establishment rhetoric was politically beneficial, Trump withdrew troops from Afghanistan more quickly than required by the agreement with the Taliban and campaigned for the presidency on the (albeit false) claim that he would bring the troops home by Christmas.

Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, virtually all of the almost two dozen candidates, including former Vice President Biden, were advocating for a complete U.S. withdrawal as well, with Biden saying during a debate in 2019, “We don’t need those troops there. I would bring them home.”

This alignment of elite and public opinion, however, was short-lived.

When Biden’s promised withdrawal went awry last summer, and the Taliban took control of Afghanistan far more quickly than anticipated, the national security establishment almost unanimously criticized the withdrawal, fearing that al Qaeda would resurge. Without U.S. troops on the ground, they claimed, the U.S. would lose the ability to gather intelligence and take action against terrorists in the region. Most national security elites argued that the withdrawal was ill-advised and Biden should have reversed course, abrogated Trump’s deal with the Taliban, and maintained thousand troops on the ground in Afghanistan.

As for the American public, while most objected to the way the withdrawal was executed (including the tragic ISIS attack resulting in the death of 13 service members), almost a year after our troops left, 60% of the American public still believe that withdrawal from Afghanistan was the right decision.

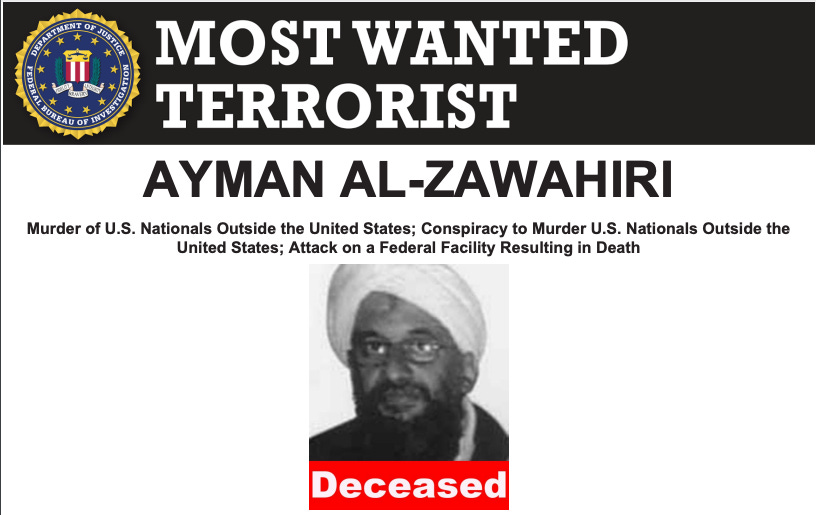

The drone strike against al Zawahiri is beneficial to national cohesion because it helps to keep U.S. counterterrorism policy in line with public opinion.

The strike shows that even without a large troop presence in Afghanistan, the U.S. was still able to gain intelligence on al Zawahiri’s whereabouts and execute a lethal attack against him. It also delivered a stark message to the Taliban: “Beware, you cannot operate a hotel (or “a base” - “al qaeda” in Arabic) for international terrorists in Kabul with impunity.” Both of these factors, if they can be sustained over time, will lend support to the ultimate decision to withdraw from Afghanistan.

And imagine, if the opposite were to have occurred - that is, if the first significant thing to happen after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan had been an al-Qaeda sponsored attack on U.S. interests. Extreme pressure would have emerged to reengage in Afghanistan, perhaps even re-inserting U.S. troops into region. Division between elite and populist opinion would have exploded.

Of course, the situation could change in an instant with one successful attack. That is the nature of terrorism. But if the United States can continue to keep a lid on al Qaeda and likeminded groups without having a large scale troop presence in places like Afghanistan, it will remove one of the grievances against the governing establishment held by the grassroots public.

While hardly a cure-all, this is good for American democracy.